These memories were written when Joan was in her eighties and are therefore not contemporaneous.

I remember my parents asking me if I’d like to go to America. What a question to ask a 7 year old! At school we had been told about red indians who lived in wigwams and I imagined something like a school visit. Of course I said yes with some enthusiasm. “You might not see Mummy and Daddy for a long time”. “That’s all right”, I said and was surprised when my answer seemed to make my mother cross. It wasn’t until I was in my 60s and read my father’s journal that I realised how they had agonised for weeks over whether to take up the Kodak(1) offer or not. The night before the final day for deciding, Daddy was on air raid duty with the Home Guard(2) . By the end of the night he had decided that, whatever happened, the family should stay together. When he arrived home he asked my mother what conclusion she had come to and it was the opposite; they should not risk keeping me in England when I had the chance to go abroad and be safe. Daddy pretended that he had thought the same... and so I was added to the Kodak list. At that time they and most other people thought the war would be over one way or another by Christmas. If they had known it would drag on for 5 years more I wonder if I would have been sent or not. If I, as a mother, were put in that position, I can’t say what I would have done.

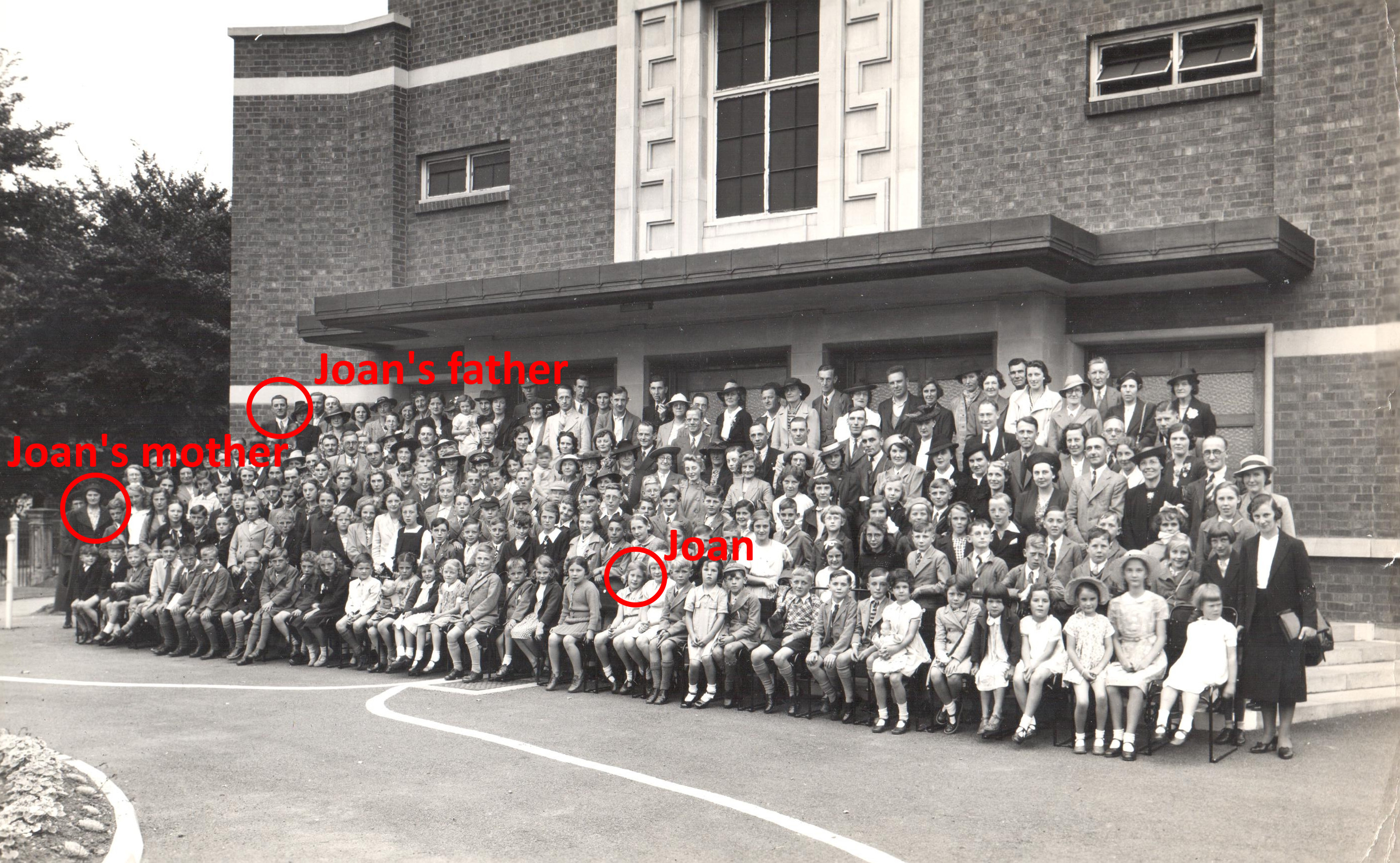

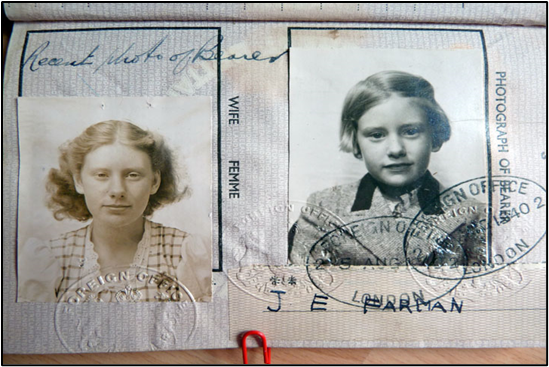

I was 8 in June 1940 and evacuated in August. Only a few things stick in my mind. We all congregated at the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square, London. We children were all together in a large hall. Our parents were standing on a huge sweeping curved staircase, looking down at us. There must have been some tears. I was just bewildered. We had to travel to Liverpool by train and because I was small I was lifted onto the luggage rack to sleep.

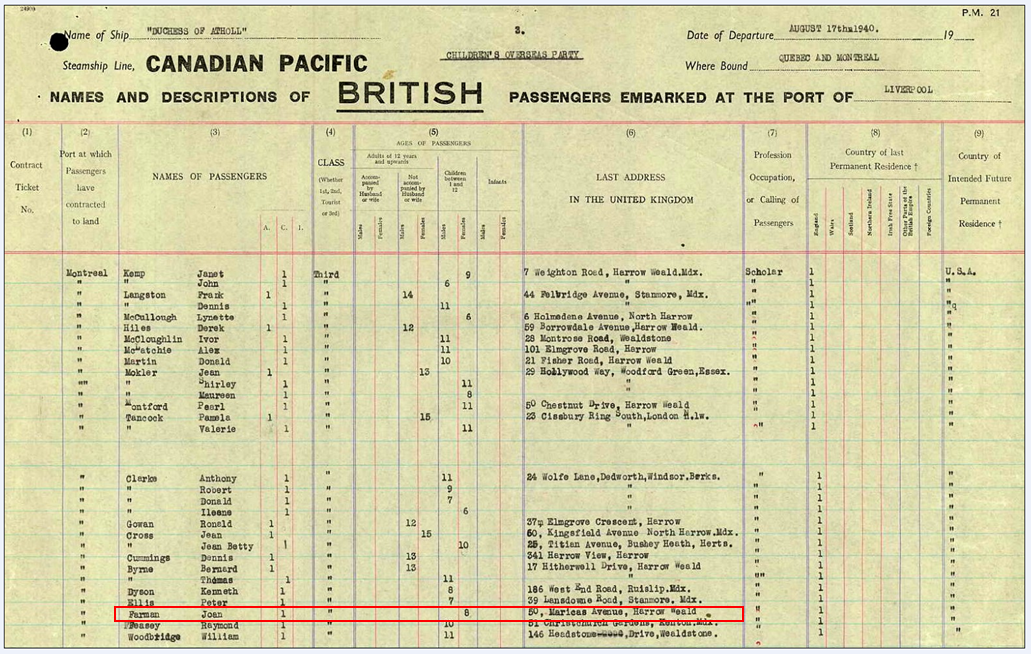

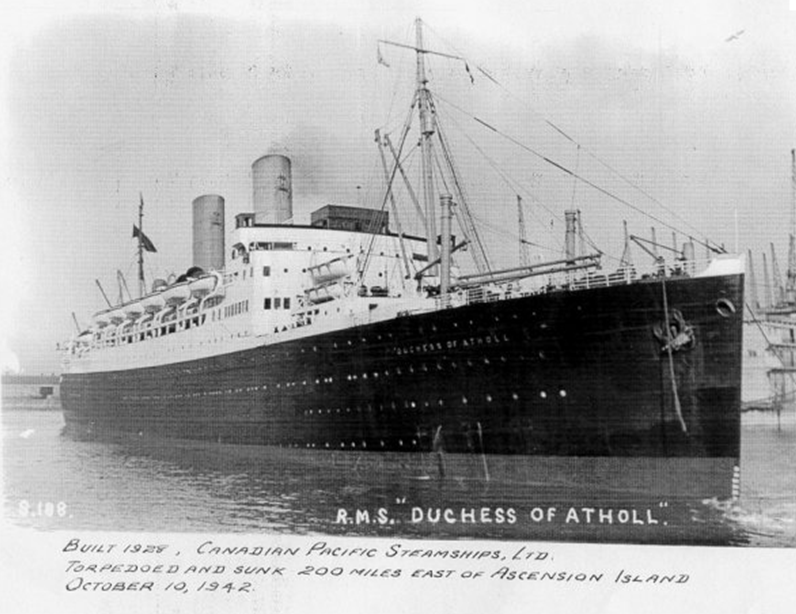

In Liverpool we boarded the RMS Duchess of Atholl which was to take us across the Atlantic. I was in a cabin with 3 other girls and had a bottom bunk. One evening there was a concert and the 12 year old girl in the bunk above mine, whose name was Pearl, was going to sing “The White Cliffs of Dover”. I wanted to go to the concert but I wasn’t allowed to because I was too young to stay up for it.

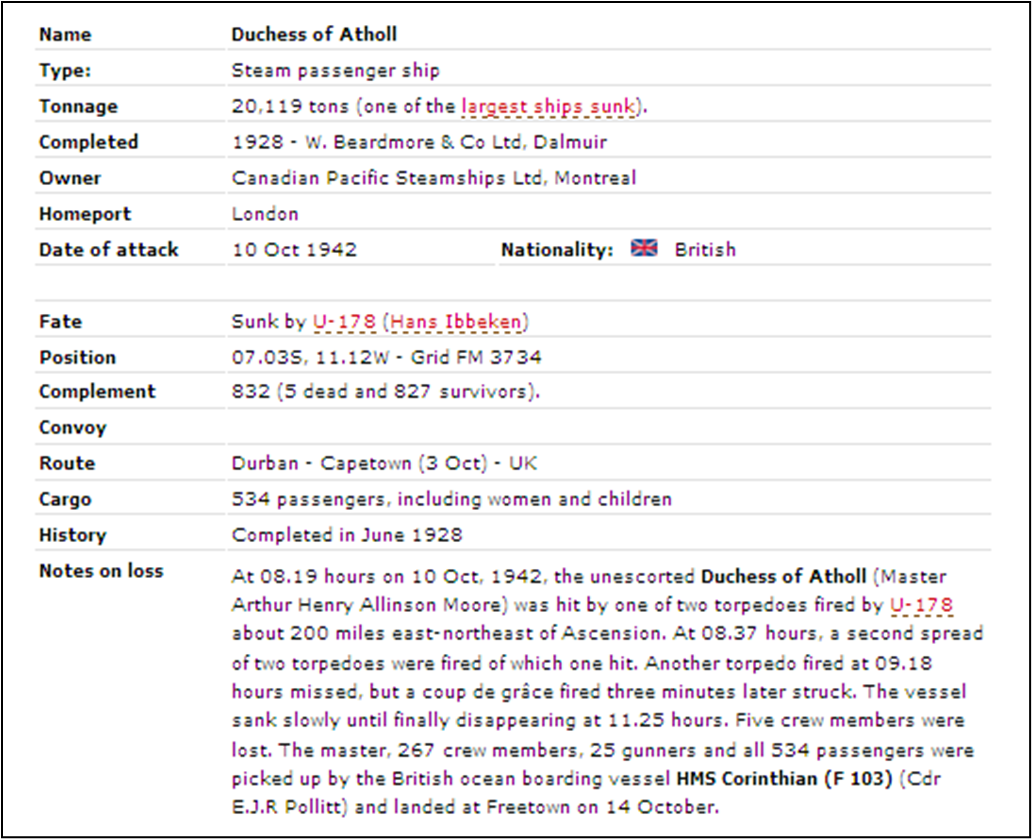

Once we had a lifeboat drill at around 2 in the morning. It was very cold and dark as we gathered on deck wearing our life jackets. Later we found that it was rather more than a drill because a German U-boat had been sighted. It had been frustrated by our protective cruisers. We were very lucky.

The most exciting event for me was seeing an iceberg, something that you never forget. It was enormous and I can picture it to this day. We were sailing as far north as possible to try to avoid enemy submarines.

Our ship sailed up the St Lawrence River as far as Montreal. At one point it was like a canal and the walls were so close you thought you could touch them. That must have been at Quebec I think. At Montreal we were put on a train to Rochester in New York State, passing through US immigration at a place called Malone.

Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck, City Historian of Rochester NY:

Committees formed on both sides of the Atlantic with prominent citizens in authoritative positions. In a very short time the United States’ impediments were removed: the Immigration law was amended and the Neutrality legislation was broadened to include “mercy ships(3)”. The British government screened thousands of children for immigration to the U.S. but refused to allow liners to sail without escort. Unwilling to divert military vessels from defense to the convoying of civilians, they appealed to the U.S. to supply the protection necessary to ensure the children's safety at sea. Some liners were accompanied by British naval vessels for a few hours out of port, but the rest were virtually alone, avoiding the areas known to be patrolled by German submarines.The evacuations had hardly begun when a ship carrying 230 children was torpedoed. Ships in transit were recalled; the program was postponed indefinitely.

The Duchess of Atholl, with me and the other Kodakids aboard had already sailed and had passed the point of no return, so we continued on our way. Luckily our escort ships were able to frighten the U-boats off. Most of the children on the ship that was sunk were from Wembley, I was told later.